In the decades after the Civil War, giant corporations and cartels began to dominate railroads, oil, banking, meat packing, and a dozen other industries. These businesses were led by entrepreneurs who, rightly or wrongly, have come to be thought of as “robber barons” out to crush their competitors, monopolize their markets, and gouge their customers. The term “robber baron” was associated with such names as J.P. Morgan and Andrew Carnegie in the steel industry, Philip Armour and Gustavas and Edwin Swift in meat packing, James P. Duke in tobacco, and John D. Rockefeller in the oil industry. They gained their market power through cartels and other business agreements aimed at restricting competition. Some formed trusts, a combination of corporations designed to consolidate, coordinate, and control the operations and policies of several companies. It was in response to the rise of these cartels and giant firms that antitrust policy was created in the United States. Antitrust policy refers to government attempts to prevent the acquisition and exercise of monopoly power and to encourage competition in the marketplace.

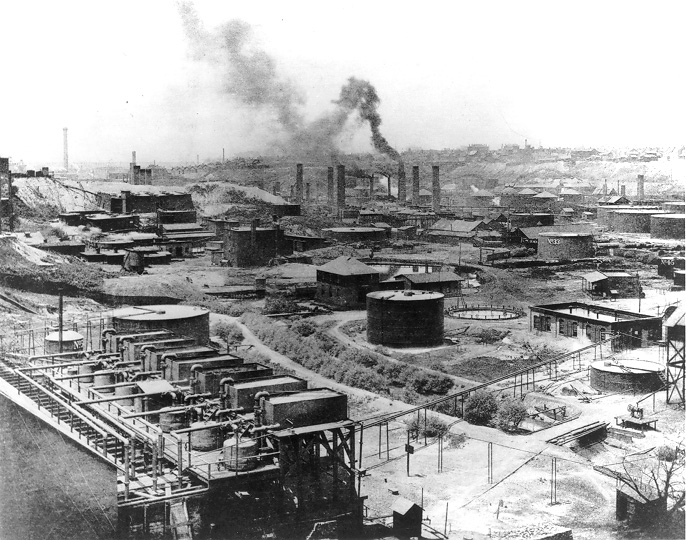

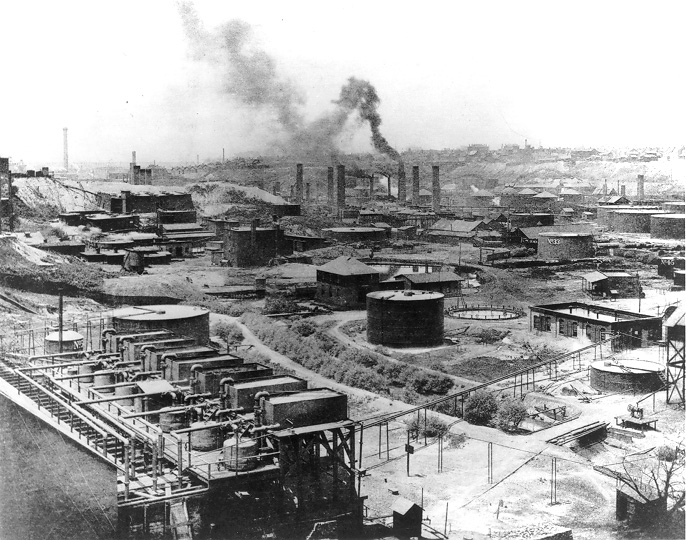

The final third of the nineteenth century saw two major economic transitions. The first was industrialization—a period in which U.S. firms became far more capital intensive. The second was the emergence of huge firms able to dominate whole industries. In the oil industry, for example, Standard Oil of Ohio (after 1899, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey) began acquiring smaller firms, eventually controlling 90% of U.S. oil-refining capacity. American Tobacco gained control of up to 90% of the market for most tobacco products, excluding cigars.

Public concern about the monopoly power of these giants led to a major shift in U.S. policy. What had been an economic environment in which the government rarely intervened in the affairs of private firms was gradually transformed into an environment in which government agencies took on a much more vigorous role. The first arena of intervention was antitrust policy, which authorized the federal government to challenge the monopoly power of firms head-on. The application of this policy, however, has followed a wandering and rocky road.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 remains the cornerstone of U.S. antitrust policy. The Sherman Act outlawed contracts, combinations, and conspiracies in restraint of trade.

An important issue in the interpretation of the Sherman Act concerns which actions by firms are illegal per se , meaning illegal in and of itself without regard to the circumstances under which it occurs. Shoplifting, for example, is illegal per se; courts do not inquire whether shoplifters have a good reason for stealing something in determining whether their acts are illegal. One key question of interpretation is whether it is illegal per se to control a large share of a market. Another is whether a merger that is likely to produce substantial monopoly power is illegal per se.

Two landmark Supreme Court cases in 1911 in which the Sherman Act was effectively used to break up Standard Oil and American Tobacco enunciated the rule of reason , which holds that whether or not a particular business practice is illegal depends on the circumstances surrounding the action. In both cases, the companies held dominant market positions, but the Court made it clear that it was their specific “unreasonable” behaviors that the breakups were intended to punish. In determining what was illegal and what was not, emphasis was placed on the conduct, not the structure or size, of the firms.

In the next 10 years, the Court threw out antitrust suits brought by government prosecutors against Eastman Kodak, International Harvester, United Shoe Machinery, and United States Steel. The Court determined that none of them had used unreasonable means to achieve their dominant positions in the industry. Rather, they had successfully exploited economies of scale to reduce costs below competitors’ costs and had used reasonable means of competition to reap the rewards of efficiency.

The rule of reason suggests that “bigness” is no offense if it has been achieved through legitimate business practices. This precedent, however, was challenged in 1945 when the U.S. Court of Appeals ruled against the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). The court acknowledged that Alcoa had been able to capture over 90% of the aluminum industry through reasonable business practices. Nevertheless, the court held that by sheer size alone, Alcoa was in violation of the prohibition against monopoly.

In a landmark 1962 court case involving a proposed merger between United Shoe Machinery and the Brown Shoe Company, one of United’s competitors, the Supreme Court blocked the merger because the resulting firm would have been so efficient that it could have undersold all of its competitors. The Court recognized that lower shoe prices would have benefited consumers, but chose to protect competitors instead.

The Alcoa case and the Brown Shoe case, along with many other antitrust cases in the 1950s and 1960s, added confusion and uncertainty to the antitrust environment by appearing to reinvoke the doctrine of per se illegality. In the government’s case against Visa and MasterCard, the government argued successfully that the behavior of the two firms was a per se violation of the Sherman Act.

The Sherman Act also aimed, in part, to prevent price-fixing , in which two or more firms agree to set prices or to coordinate their pricing policies. For example, in the 1950s General Electric, Westinghouse, and several other manufacturers colluded to fix prices. They agreed to assign market segments in which one firm would sell at a lower price than the others. In 1961, the General Electric–Westinghouse agreement was declared illegal. The companies paid a multimillion-dollar fine, and their officers served brief jail sentences. In 2008, three manufactures of liquid crystal display panels—the flat screens used in televisions, cell phones, personal computers, and such—agreed to pay $585 million in fines for price fixing, with LG Display paying $400 million, Sharp Corporation paying $120 million, and Chunghwa Picture Tubes paying $65 million. The $400 million fine to LG is still less than the record single fine of $500 million paid in 1999 by F. Hoffman-LaRoche, the Swiss pharmaceutical company, in a case involving fixing prices of vitamin supplements.

Concerned about the continued growth of monopoly power, in 1914 Congress created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), a five-member commission that, along with the antitrust division of the Justice Department, has the power to investigate firms that use illegal business practices.

In addition to establishing the FTC, Congress enacted new antitrust laws intended to strengthen the Sherman Act. The Clayton Act (1914) clarifies the illegal per se provision of the Sherman Act by prohibiting the purchase of a rival firm if the purchase would substantially decrease competition, and outlawing interlocking directorates, in which there are the same people sitting on the boards of directors of competing firms. More significantly, the act prohibits price discrimination that is designed to lessen competition or that tends to create a monopoly and exempts labor unions from antitrust laws.

The Sherman and Clayton acts, like other early antitrust legislation, were aimed at preventing mergers that reduce the number of firms in a single industry. The consolidation of two or more producers of the same good or service is called a horizontal merger . Such mergers increase concentration and, therefore, the likelihood of collusion among the remaining firms.

The Celler–Kefauver Act of 1950 extended the antitrust provisions of earlier legislation by blocking vertical mergers , which are mergers between firms at different stages in the production and distribution of a product if a reduction in competition will result. For example, the acquisition by Ford Motor Company of a firm that supplies it with steel would be a vertical merger.

The “bigness is badness” doctrine dominated antitrust policy from 1945 to the 1970s. But the doctrine always had its critics. If a firm is more efficient than its competitors, why should it be punished? Critics of the antitrust laws point to the fact that of the 500 largest companies in the United States in 1950, over 100 no longer exist. New firms, including such giants as Walmart, Microsoft, and Federal Express, have taken their place. The critics argue that the emergence of these new firms is evidence of the dynamism and competitive nature of the modern corporate scene.

There is no evidence to suggest, for example, that the degree of concentration across all industries has increased over the past 25 years. Global competition and the use of the internet as a marketing tool have increased the competitiveness of a wide range of industries. Moreover, critics of antitrust policy argue that it is not necessary that an industry be perfectly competitive to achieve the benefits of competition. It need merely be contestable —open to entry by potential rivals. A large firm may be able to prevent small firms from competing, but other equally large firms may enter the industry in pursuit of the high profits earned by the initial large firm. For example, Time Warner, primarily a competitor in the publishing and entertainment industries, has in recent years become a main competitor in the cable television market.

Currently, the Justice Department follows guidelines based on the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI). The HHI, introduced in an earlier chapter, is calculated by summing the squared percentage market shares of all firms in an industry, where the percentages are expressed as whole numbers (for example 30% would be expressed as 30). The higher the value of the index, the greater the degree of concentration. Possible values of the index range from 0 in the case of perfect competition to 10,000 ( =1002 ) in the case of a monopoly.

Current guidelines stipulate that any industry with an HHI under 1,000 is unconcentrated. Except in unusual circumstances, mergers of firms with a postmerger index under 1,000 will not be challenged. The Justice Department has said it would challenge proposed mergers with a postmerger HHI between 1,000 and 1,800 if the index increased by more than 100 points. Industries with an index greater than 1,800 are deemed highly concentrated, and the Justice Department has said it would seek to block mergers in these industries if the postmerger index would increase by 50 points or more. Table 16.1 “The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index and Antitrust Policy” summarizes the use of the HHI by the Justice Department.

Table 16.1 The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index and Antitrust Policy

| If the postmerger Herfindahl-Hirschman Index is found to be… | then the Justice Department will likely take the following action. |

|---|---|

| Unconcentrated ( <1,000) | No challenge |

| Moderately concentrated (1,000–1,800) | Challenge if postmerger index changes by more than 100 points. |

| Highly concentrated (>1,800) | Challenge if postmerger index changes by more than 50 points. |

The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have adopted the following guidelines for merger policy based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index.

U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, 1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, issued April 2, 1992, revised April 8, 1997.

One difficulty with the use of the HHI is that its value depends on the definition of the market. With a sufficiently narrow definition of the market, even a highly competitive market could have an HHI close to the value for a monopoly. The late George Stigler commented on the difficulty in a fanciful discussion of the definition of the relevant market for cameras:

“Consider the problem of defining a market within which the existence of competition or some form of monopoly is to be determined. The typical antitrust case is an almost impudent exercise in economic gerrymandering. The plaintiff sets the market, at a maximum, as one state in area and including only aperture-priority SLR cameras selling between $200 and $250. This might be called J-Shermanizing the market, after Senator John Sherman. The defendant will in turn insist that the market be world-wide, and include not only all cameras, but all portrait artists and all transportation media, since a visit is a substitute for a picture. This might also be called T-Shermanizing the market, after the Senator’s brother, General William Tecumseh Sherman. Depending on who convinces the judge, the concentration ratio will be awesome or trivial, with a large influence on the verdict” (Stigler, G. J., 1982).

Of course, the definition of the relevant market is not a matter of arbitrarily defining the market as absurdly narrow or broad. There are economic tests to determine the range of goods or services that should be included in a particular market. Consider, for example, the market for refrigerators. Given the relatively low cost of shipping refrigerators, the relevant area might encompass all of North America, given the existence of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which establishes a tariff-free trade zone including Canada, the United States, and Mexico. What sorts of goods should be included? Presumably, any device that is powered by electricity or by natural gas and that keeps things cold would qualify. Certainly, a cool chest that requires ice that people take on picnics would not be included. The usual test is the cross price elasticity of demand. If it is high between any two goods, then those goods are candidates for inclusion in the market.

Should the entire world be the geographic region for the market for refrigerators? That is an empirical question. If the cross price elasticities for refrigerator brands worldwide are high, then one would conclude that the world is the relevant geographical definition of the market.

In the 1980s both the courts and the Justice Department held that bigness did not necessarily translate into badness, and corporate mergers proliferated. In the period 1982–1989 there were almost 200 mergers and acquisitions of firms whose value exceeded $1 billion. The total value of these companies was nearly half a trillion dollars.

Megamergers continued in the 1990s and into the 21st-century. In 2000, there were 212 mergers valued at $1 billion or more and in 2006 nearly that many. Since then, merger activity has decreased, in part due to turmoil in financial markets (Krantz, M., 2006; Krantz, M., 2007).

According to what basic principle did the U.S. Supreme Court find Eastman Kodak not guilty of violating antitrust laws? According to what basic principle did the Court block the merger of Brown Shoe Company and one of its competitors, United Shoe Machinery? Do you agree or disagree with the Court’s choices?

The Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission spend a great deal of money enforcing U.S. antitrust laws. Firms defending themselves may spend even more.

The government’s first successful use of the Sherman Act came in its action against Standard Oil in 1911. The final decree broke Standard into 38 independent companies. Did the breakup make consumers better off?

In 1899, Standard controlled 88% of the market for refined oil products. But, by 1911, its share of the market had fallen to 64%. New discoveries of oil had sent gasoline prices down in the years before the ruling. After the ruling, gasoline prices began rising. It does not appear that the government’s first major victory in an antitrust case had a positive impact on consumers.

In general, antitrust cases charging monopolization take so long to be resolved that, by the time a decree is issued, market conditions are likely to have changed in a way that makes the entire effort seem somewhat frivolous. For example, the government charged IBM with monopolization in 1966. That case was finally dropped in 1982 when the market had changed so much that the original premise of the case was no longer valid. In 1998 the Department of Justice began a case against against Microsoft, accusing it of monopolizing the market for Internet browsers by bundling the browser with its operating system, Windows. A trial in 2000 ended with a judgment that Microsoft be split in two with one company having the operating system and another having applications. An appeals court overturned that decision a year later.

Actions against large firms such as Microsoft are politically popular. However, neither policy makers nor economists have been able to establish that they serve consumer interests.

We have seen that the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission have a policy of preventing mergers in industries that are highly concentrated. But, mergers often benefit consumers by achieving reductions in cost. Perhaps the most surprising court ruling involving such a merger came in 1962 when the Supreme Court ruled that a merger in shoe manufacturing would achieve lower costs to consumers. The Court prevented the merger on grounds the new company would be able to charge a lower price than its rivals! Clearly, the Court chose to protect firms rather than to enhance consumer welfare.

What about actions against price-fixing? The Department of Justice investigates roughly 100 price-fixing cases each year. In many cases, these investigations result in indictments. Those cases would, if justified, result in lower prices for consumers. But, economist Michael F. Sproul, in an examination of 25 price-fixing cases for which adequate data were available, found that prices actually rose in the four years following most indictments.

Economists Robert W. Crandall and Clifford Winston have asked a very important question: Has all of this effort enhanced consumer welfare? They conclude that the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission would best serve the economy by following a policy of benign neglect in cases of monopolization, proposed mergers, and efforts by firms to exploit technological gains by lowering price. The economists conclude that antitrust actions should be limited to the most blatant cases of price-fixing or mergers that would result in monopolies. In contrast, law professor Jonathan Baker argued in the same journal that such a minimalist approach could be harmful to consumer welfare. One argument he makes is that antitrust laws and their enforcement create a deterrence effect.

A recent paper by Orley Ashenfelter and Daniel Hosken analyzed the impact of five mergers in the consumer products industry that seemed to be most problematic for antitrust enforcement agencies. In four of the five cases prices rose following the mergers and in the fifth case the merger had little effect on price. While they do not conclude that this small study should be used to determine the appropriate level of government enforcement of antitrust policy, they state that those who advocate less intervention should note that the price effects were not negative, as they would have been if these mergers were producing cost decreases and passing them on to consumers. Those advocating more intervention should note that the price increases they observed after these mergers were not very large.

Sources: Orley Ashenfelter and Daniel Hosken, “The Effect of Mergers on Consumer Prices: Evidence from Five Selected Cases,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 13859, March 2008; James B. Baker, “The Case for Antitrust Enforcement,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17:4 (Fall 2003): 27–50; Robert W. Crandall and Clifford Winston, “Does Antitrust Policy Improve Consumer Welfare? Assessing the Evidence,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17:4 (Fall 2003): 3–26; Michael F. Sproul, “Antitrust and Prices,” Journal of Political Economy, 101 (August 1993): 741–54.

In the case of Eastman Kodak, the Supreme Court argued that the rule of reason be applied. Even though the company held a dominant position in the film industry, its conduct was deemed reasonable. In the proposed merger between United Shoe Machinery and Brown Shoe, the court clearly chose to protect the welfare of firms in the industry rather than the welfare of consumers.

Krantz, M., “Big Day for Buyouts, But Tepid Pace Forecase To Continue; Credit Crunch and Other Economic Fears Take Toll,” USA Today, December 18, 2007, p. 1B.

Krantz, M., “Merger Market Arrives At ’Good spot’; 2006 the Busiest Takeover Year Since End Of ’90s Bull,” USA Today, November 7, 2006, p. 3B.

Stigler, G. J., “The Economists and the Problem of Monopoly,” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 72:2 (May 1982): 8–9.

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.